- Home

- Susan Stellin

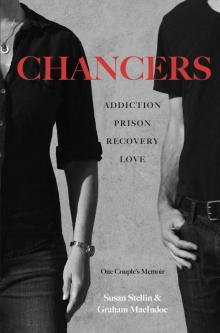

Chancers

Chancers Read online

Copyright © 2016 by Susan Stellin and Graham MacIndoe

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

BALLANTINE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Stellin, Susan, author. | MacIndoe, Graham, author.

Title: Chancers : addiction, prison, recovery, love: one couple’s memoir / Susan Stellin and Graham MacIndoe.

Description: First edition. | New York : Ballantine Books, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016003606 | ISBN 9781101882740 (hardback) | ISBN 9781101882757 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Stellin, Susan. | MacIndoe, Graham | Drug addicts—United States—Biography. | Drug addicts—Rehabilitation—United States—Biography. | Drug addicts—Family relationships. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | PSYCHOLOGY / Psychopathology / Addiction. | FAMILY & RELATIONSHIPS / Love & Romance.

Classification: LCC HV5805.S75 A3 2016 (print) | LCC HV5805.S75 (ebook) | DDC 363.29092/2—dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016003606

ebook ISBN 9781101882757

Cover design: Pure+Applied

Cover photograph: Graham MacIndoe

randomhousebooks.com

v4.1

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Authors’ Note

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One: We

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Part Two: Ourselves

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part Three: Us

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Epilogue

Dedication

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

AUTHORS’ NOTE

Any memoir is subjective, and this one is no exception, but the events described in the following pages did actually happen. We did not invent scenes or characters, although we did change most people’s names—except for public figures and Graham’s son, because he asked us to use his real name. In order to reconstruct situations and conversations, we relied on email messages, letters, notes, court documents, and input from people who appear in the book, but in some places, the dialogue is based solely on our memories. Some of the letters and email messages quoted have been condensed or edited slightly for clarity. We are grateful for the permission we received to include this correspondence, and for our families’ willingness to expose parts of their lives alongside ours.

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 A.M. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.”

—Joan Didion, “On Keeping a Notebook”

PROLOGUE

January 2011

York County Prison, Pennsylvania

I’m sitting in a rental car outside a prison in Pennsylvania, where my ex-boyfriend is being held by the Department of Homeland Security. It’s a frigid day in January, the winter back-to-back blizzards buried the Northeast, but I’ve driven down from Brooklyn during a break in the storms, arriving just as the light is starting to fade.

By 5 P.M., the parking lot where I’m waiting has turned ominous, prison floodlights interrogating a landscape of black and gray.

Inside, Graham can’t see daylight, a frequent complaint during the five months he’s been a prisoner here. The only windows in the dorm are up near the ceiling—too high for any kind of view. He once described how the inmates would stand against the wall whenever a strip of sunlight entered at an angle. As the sun lowered, the light moved higher on the wall, the men following it with their faces until it was out of reach.

Hearing stories like this has made me appreciate the things you take for granted when you’re free.

Last summer, I’d watch the sun set across the East River as I ran along the Brooklyn waterfront, newly conflicted about the Statue of Liberty in the distance. In the fall, I noticed the leaves swirling around the sidewalk, stopping to pick one up so I could share the seasonal shift with Graham. At home I set the leaf on a piece of paper and carefully traced around the edges, knowing I couldn’t send him the real thing. Technically, inmates aren’t allowed to receive drawings—one of many rules I had to learn—but my tracing made it through the mailroom. Many letters didn’t.

The ones that did were often tough to read.

“I just wish I could breathe some fresh air, feel the wind, smell the trees, feel the sun or the rain on my skin,” Graham wrote to me, just after he arrived at the Pennsylvania prison. “Every day here is very painful, lonely and long—no matter what you do to break it up, there’s a limit to how you can use up 16 hours a day with nothing to do.”

I was sympathetic to his complaints—shocked, really, at how he and the other prisoners were treated. But after five months of helping him and fighting for his release, I’m worn down by the whole ordeal. It has also taken a toll on me.

My cellphone rings. The noise seems louder in the car, startling me as I fumble to answer quickly. I can tell from the number that it’s Graham, which means I can’t call him back if I miss it.

“You have a call from an inmate at York County Prison,” the familiar recording begins. “Press one to accept the charges, press two to decline….”

I hold the phone closer to make sure I press the right button, anxious because Graham shouldn’t be calling me now. He should be in a van heading to the parking lot, or busy dealing with paperwork, or changing out of his prison uniform into street clothes. I’m here to pick him up because he’s supposed to be released.

“They haven’t called my name yet!” Graham shouts. I move the phone a little farther from my ear. “It’s after five and they haven’t called my name! They’ve called other names—ages ago—but not mine. I can’t fucking believe it, what is going on?”

“Don’t yell,” I tell him, reflexively worried—even now—that he’ll once again lose phone privileges. “I’m in the car, in the parking lot. The van isn’t here yet.”

By now I’m an expert at remaining calm, offering support, being optimistic. Back when we were together, Graham looked on the bright side and I imagined every possible worst-case scenario, but I’m starting to panic, too. I’ve made this trip once before—and drove home alone when Graham didn’t get released—so this time I told our lawyer I wasn’t leaving Brooklyn until the paperwork had actually been signed.

“Go get your man,” he’d said, when he called earlier today. “The judge just signed the order. They’re going to release Graham before six.”

I look at the clock glowing on the dashboard: It’s 5:13.

“Everybody is asking why I’m still here,” Graham says. “I have no idea, no one has told me a fucking thing. I’m just sitting here waiting—all fucking day, watching the clock. I cannae take this anymore.”

Graham’s Scottish accent is always stronger when he’s venting, despite living in Brooklyn for almost twe

nty years.

“Go talk to your counselor,” I suggest. “Maybe he can find out what’s going on. The visiting area is closed so I can’t do much out here.”

What I don’t tell him is that I don’t want to leave the car in case I miss the white van I’m expecting, hoping it’s just running late. The paralegal had warned me that if I wasn’t right there to collect Graham when the van brought him to the parking lot, he’d be driven to the bus station and dropped off—with no coat, no ID, and no money.

That is one of the cruelties of a system operating in the shadows of the law: Even though Graham was picked up by Homeland Security in New York City last August, it’s his responsibility to get back home.

Not that he has a home to return to. He lost his house during his downward spiral toward prison, so he’s going to stay with me until he sorts things out.

Thinking about how that cohabitation is going to work makes my anxiety kick into a higher gear. We broke up fours years ago and reconnected when I found out Graham was locked up. That news came as a relief—I thought he was dead when he disappeared—but I had no idea what I was getting into when I finally tracked him down.

Nearly half a year later, setting Graham free has practically become a full-time job. I didn’t expect to fall back in love with him, and we’ve sort of danced around what’s going to happen once he’s out. Until a few days ago, we weren’t even sure he’d get released from prison—theoretically, any moment now.

It’s almost six when I notice headlights coming up the road, but it’s too dark to tell if it’s a van and too soon after Graham’s call for him to possibly be inside. At this point, I know the prison bureaucracy moves at a glacial pace, so there’s no way Graham made it from his dorm to the curb in half an hour.

As the headlights arc toward the parking lot, completing a right turn, my heart drops: It’s definitely a white van. I try to summon a shred of hope as I open the car door.

By the time I shuffle across the icy pavement, the van has parked, engine idling. An officer dressed all in black is standing next to the side door, already calling out names. One by one, a few men stumble out—I wonder how that must feel, after months or years of dreaming about this day. But no one is stopping for a long hug or a deep breath of fresh air; family members steer the men toward cars that are still running, mindful of how easily freedom can be snatched away.

I count three—no, four—prisoners who have been released, try to calculate how many seats might be left in the van. As the officer starts to slide the door closed, I step forward and say, “Wait!”

“I’m here to pick someone up,” I tell him, trying to sound confident, assertive. But when I say Graham’s name, there’s a doubtful question mark at the end.

“He’s not on the list,” the officer says, barely glancing at his clipboard.

In that moment, I feel an unworthy kinship with the victims of authoritarian regimes, well aware that my sense of persecution is at odds with the suburban setting: There’s a mall with a Gap and a food court across the street, I have a room at a nearby Hampton Inn.

I explain that Graham is supposed to be released today, that the judge signed the order, that I’ve driven to Pennsylvania twice to pick him up, that this is wrongful imprisonment. My outrage is no match for the power of a functionary who couldn’t care less.

“You’ll have to work it out on Tuesday,” the officer tells me, slamming the van door. “Monday is a holiday, so no one who can help you will be in until then.”

I want to scream every obscenity I can think of, grab his shoulders and shake him, unload all the frustration of the past half year. But I just stand there shivering as he climbs back into the van. He doesn’t give a shit about me—I’m no one to him.

After he drives off, I’m not ready to concede defeat, so I spend another hour outside the prison, shouting at guards through intercoms, calling our lawyer in New York, pleading with night shift employees entering the building to help me. But there’s nothing anyone can do. Graham is not on the list.

Part One

WE

“The obscure we see eventually,

the completely apparent takes longer.”

—Edward R. Murrow

CHAPTER ONE

Summer 2002

Montauk, New York

When Graham and I first met, in the summer of 2002, it definitely wasn’t love at first sight. We were both part of a group of loosely connected friends who shared a beach house in Montauk, which at that point was still the affordable, laid-back alternative to the Hamptons. As one friend put it: In the Hamptons, you wore a sweater draped over your shoulders; in Montauk, you tied a hoodie around your waist. In either case, it was a way to escape New York City when the heat became oppressive.

About a dozen of us rented a house just uphill from the beach, alternating weekends according to a schedule plotted out at the beginning of the summer—and then promptly abandoned. I had signed up for four weekends, thinking I’d overlap with my sister and a few friends, but as everyone’s plans shifted, I ended up spending two of those weekends with people I didn’t really know.

That was partly the point of doing a share house—mixing it up a bit, maybe indulging in a summer romance—but our group was pretty tame by beach house standards. Most of us were in our thirties, working in advertising, media, photography, or film. I was thirty-three and doing well as a freelance writer, but I wasn’t having much luck finding a partner.

The memories I have of that summer are like slides clicking around a circular tray in an old projector, images that are a bit fuzzy on the screen lit up in my mind. But the first time I met Graham, there’s no doubt he made an impression. A thirty-nine-year-old Scotsman, he was gregarious and self-confident, if a bit cocky about his success as a photographer. Lean and energetic, he talked practically nonstop—funny anecdotes about the people whose portraits he’d taken and frank opinions about American culture. His girlfriend, Liz, was twenty-five and much more aloof, so they struck me as an odd match as a couple.

That weekend, I remember staying up late with Graham and his English friend Tom, empty beer bottles on the kitchen table outnumbering the housemates who had drifted off to bed—including Liz. At first glance, the scene might’ve seemed like typical Saturday night excess, but their banter had a bittersweet context. Tom’s wife had died of cancer a few years earlier, leaving him to raise their young son, and he was moving back to London to be closer to his family. Graham was divorced and had an eleven-year-old son who was spending the summer with his grandparents in Scotland. It was one of the last weekends Graham and Tom would be together on the same side of the Atlantic.

I lingered long after I stopped drinking, just taking in the intensity of their friendship—laughter that brought tears, a crescendo of voices competing to make a point, a shared history weighed down by the ballast of pain and parenting. I had a wide circle of friends, relationships nurtured in the absence of kids or a husband, but this raucous expression of affection felt foreign, a brand of British boisterousness I hadn’t been exposed to reading novels by Jane Austen and Virginia Woolf. It reminded me of the late nights my old boyfriend Ethan and I spent with friends when we were living in Argentina—that unfiltered passion I associated more with Latin America than Britain.

When I finally left the table, it felt like stepping away from a campfire, their voices receding but not quite fading as I walked down the hall. Even after I settled into a twin bed with damp sheets, I could still hear Graham and Tom in the kitchen, arguing about politics or art or the details of some long-ago road trip. It was the soundtrack of an impending end, when suddenly everything and nothing else mattered.

Later that summer, my friend Scott and I tagged along with Graham and Liz to an art opening in East Hampton, riding in Graham’s red Volkswagen with music blaring. The Guild Hall gallery scene was a blur of cocktail party mingling and art-crowd conversation, all the high heels and sundresses making me self-conscious about my jeans and flip-flops. Afterward,

the exhibition curator invited us back to the house where he was staying, a stately colonial overlooking Town Pond. We had more drinks on the deck of his garret apartment; other people stopped by and left. I was starving, but eating didn’t seem to be on anyone else’s agenda.

By the time Graham was ready to call it a night, it occurred to me that we were all too drunk to drive, but I was too tired to raise the issue—all I wanted to do was sleep. On the way back to Montauk, the car windows rolled down to let in a sobering, exhilarating rush of air, I knew that it was a reckless ride, that I was throwing my usual caution to the wind. But by that summer after 9/11, my concept of danger had shifted: After a year of reading and writing about the survivors and victims of that attack, I didn’t really see the point of calculating risk. It was the kind of thing I did as a teenager in Michigan, riding in cars with boys who shouldn’t have been behind the wheel.

The last scenes I remember from Montauk are actually captured on film; Scott took pictures Labor Day weekend and gave me copies of his prints. It was cold and windy but Graham’s son, Liam, was back from Scotland and they decided to go for a swim, so a few of us followed them down to the beach. We were wearing fleece jackets and sweaters, but Graham and Liam stripped to their shorts, diving into the foamy fury of waves. As soon as they popped up, the current carried them in a line parallel to the shore—two slim bodies no match for the rough sea. They paddled and splashed back to land, ran toward us, then dove in again. Over and over, their bare feet slapping the wet sand as they ran past.

I grew up around lakes—swimming ever since I was two—but I never quite embraced the ocean. On a windy day, I found the unpredictability of the waves unnerving. But Liam seemed to be loving it; he and Graham were both laughing and trying to get the rest of us to join in, but none of us were tempted to leave our perch on a dry berm of sand. We were content to be watching; Graham and Liam were living. There was a part of me that envied them, that adrenaline rush of getting carried away.

Chancers

Chancers