- Home

- Susan Stellin

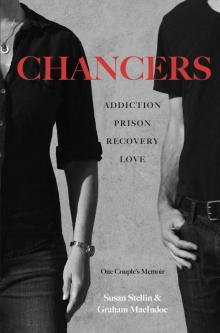

Chancers Page 6

Chancers Read online

Page 6

—

THE FIRST THING I do when I get home is go straight out and cop. For a second on the plane, I thought maybe I wouldn’t—I had this idea that I could just white-knuckle it and deal with the withdrawal on my own. But by the time I get to Brooklyn, I’m too sick to fight the cravings, and walking into my empty house makes any thought of trying to get clean disappear. I get cash from the ATM at the deli around the corner and head over to the projects—quicker than waiting for a dealer.

Once I’ve gotten myself straight, I download our holiday pictures to my computer—Susan coming out of the ocean in her bikini, the two of us sitting by a canal in Honolulu, me kissing her on the beach in Kauai. We look so happy together I feel like biking up to her apartment and surprising her, but it’s freezing out so she’d probably think I was mental.

Instead, I email her some of the best photos and upload the rest to an online album, sending her the link. It’s after 1 A.M. when I finally get a message back—short and to the point: “Hmm…this link doesn’t work. Don’t worry about sending any more pics tonite. I’m going to sleeeeeep. Miss you already!”

Well, at least she misses me, but I wish she were here. It’s gonna be weird sleeping alone again. After staying up most of the night—back to my bad habits—I finally crash on the couch. I don’t wake up until I hear the front door bang and Liam burst in. At first I panic, wondering if I’ve left any drugs lying around, then I relax when I see that I didn’t.

“Hi, sunshine,” I say, standing up and giving him a hug. I used to hum that Stevie Wonder song to him when he was a baby: You are the sunshine of my life….Now that he’s almost six feet tall, wearing cargo pants and a hoodie—with no coat, even in February—that nickname doesn’t quite fit. But I can’t let go of it, and I am always happy to see him.

“Hey, Dad. How was your trip?”

“Brilliant. What’s up with you? Is your mum away?”

He usually spends weekends with me and stays with her during the week, but she travels for work so sometimes things get shuffled around.

“No, she’s in town. I just came by to pick up some books.”

“Oh really?” I ask, ruffling his thick curly hair. “You were here studying while I was gone?”

“Actually, I wasn’t over here at all,” he says, grabbing my shoulders and grinning. “They’re library books I left here. I need them for a project that’s due tomorrow.”

“Well, I’m glad to see you’re not leaving things till the last minute.”

I try to get him to open up about his classes and what else he’s been doing, but he dodges my questions, asking me about Hawaii instead. So I show him some of the photos and we talk about what he wants to do for spring break—then I remember a message I got from one of his teachers.

“By the way, how come I got a call about you missing class?”

“I dunno….When was it? I haven’t skipped any classes—it must be a mistake.”

His defensiveness reminds me of my own attitude as a teenager—at his age I was constantly getting in trouble. But Liam doesn’t have that same rebellious streak so I don’t want to be too hard on him, especially since we haven’t spent as much time together since Susan started coming around.

“We can talk about it later,” I tell him, deciding to let it drop. “Do you want to do something this weekend? We could go to the arcade in Chinatown.”

“Maybe. Can Jason stay over on Saturday?”

Normally I wouldn’t mind—Jason is like a brother to him, he’s also an only child. But right now it feels like Liam is playing me so I’m a bit reluctant to give up some of our weekend time.

“Let me see if Susan is going to be here,” I say, reaching for the phone buzzing in my pocket. “But it’d be nice if we could hang out at some point.”

“We will,” he says. Sensing my distraction, he kisses my cheek and disappears downstairs to his room. A few minutes later he leaves through the door under the stoop, shouting, “Bye, Dad!” as it slams. His quick exit makes me wonder if he really did come by to get books, but there’s no point going to the front window to check. He was on his skateboard so he’ll be halfway to his mother’s house by now—or wherever he was headed so fast.

I feel like I never quite know what’s going on with him, not like I did when he was collecting Pokémon cards and begging me to buy him a Game Boy. Some of that’s my fault—I know my drinking was hard on him, and bouncing between two parents must be a pain in the ass. He seems to like Susan, which is a relief, but it’s got to be weird when your dad is totally caught up in a new relationship just as the main thing on your mind is girls.

I’ve tried to let him know he can talk to me about anything—we’ve had conversations about peer pressure and contraception and respect, all things I never talked about with my parents. At least I know he’s gotten the message about safe sex. The night Susan came by to look at the contact sheets for her book photo, Liam told me he’d left something for me under a pile of magazines, “just in case.” Turns out it was a condom. He had an assignment to buy condoms for a sex ed class—to get over being embarrassed, I guess—so he passed one off to me.

He’s very protective of me that way, and I’m probably too lax with him. I know he’s been through a lot, so I try to make it up to him by not being one of those tough dads. I suppose it makes things easier for me as well. I give him space so he’ll give me space, I don’t challenge him so he doesn’t challenge me. It’s a pattern we fell into when I was drinking too much.

But he’s fifteen now, with a life of his own, going out a lot more with his pals. I sometimes wonder if I’m cutting him too much slack—just as he’s starting to push back a bit. He’s mentioned my late nights, the fact that I haven’t been working lately, the friends that have drifted away. And now with Susan in the picture, I’ve got both of them keeping tabs on me. Things are starting to get a lot more complex.

CHAPTER FOUR

March 2006

Upper West Side, Manhattan

When I looked at the photos Graham took of us in Hawaii, I thought of Duane Michals—a photographer who writes captions to go along with his pictures. In one, a couple is sitting on the edge of a bed, entwined but fully clothed. The text says: “This photograph is my proof. There was that afternoon, when things were still good between us. And she embraced me, and we were so happy….”

Our pictures reminded me of that image. We were happy. Things were good. The photos proved it.

There were lots of shots of us together—holding hands on the beach in Kauai, side by side in a hot tub on the North Shore. But the ones that became my proof were the photos I took of Graham: tan, healthy, smiling in the saturated light just before sunset.

In one of my favorite pictures, he’s walking ahead of me toward the surf, his arms outstretched in a perfect T, his camera slung over his shoulder. It’s a moment of pure bliss, like he wanted to gather up every ray of sunlight, every drop of salty mist, embrace the whole horizon and pull it close.

It had rained and water had collected in a dip in the beach behind him, so I was trying to capture his reflection when I took the photo. But I only caught part of it—an arm, his head, and his torso. Later, I noticed that it looked like the wet sand was wiping away the rest of the reflection, as if already erasing the moment.

—

AS SOON AS we got back to New York, I had to put our relationship on the back burner and turn my attention to work. The trip had been great, just what I needed—well, except for our last day in Honolulu. I thought Graham had gotten some kind of stomach bug, but that didn’t really explain his anxious mood. I assumed he was also in a funk about our vacation ending; I was, too. The difference was, I brushed it off and moved on.

My book was due out in just over a month, so I didn’t have much time to think about anything else. I was busy sending out emails, building a website, and trying to drum up publicity, contacting every writer and editor I knew. Since I was a freelancer, ten days off had put a dent in my in

come, so I was also hustling for work.

Graham understood why I was holed up in my home office; I was actually surprised by how supportive he was of my book. It was a travel planning guide, not an exposé about some injustice in the world, but he threw himself into the promotional frenzy as if I’d written a future bestseller: designing posters he planned to paste up all over the city, printing copies of the cover on T-shirts, and sending me links to potential reviewers. I was almost embarrassed by all the effort.

To me, his photography seemed like more of an art form in the hierarchy of creative pursuits, at least compared to the type of journalism I’d done—mostly, advice about technology and travel. But he viewed writing as the tougher endeavor, expressing the difference in a way I’d remember whenever I couldn’t string together a coherent sequence of words.

“I’ve got the whole world to make a picture,” he told me. “You only have twenty-six letters.”

The fact that he wasn’t taking many pictures seemed to weigh on him, so I was trying to encourage him to kick-start his own career. But he resisted the return to reality, hoping to follow up our Hawaiian holiday with another escape. Four days after we got back, he started asking about planning a trip to Nevada, then suggested we visit a friend of his in Japan.

Trying to recapture our tropical romance, he rode his bike up to my apartment one wintry night, presenting me with two coconuts and a box of cocktail umbrellas. It turns out street vendors aren’t just showing off for tourists when they thwack at a coconut with a machete; we tried every knife in my kitchen before Graham finally resorted to drilling a hole in one end. I liked that he was handy—unlike most New York men—but power tools didn’t quite spark the mood he envisioned, so I made hot chocolate and we poked our umbrellas into marshmallows instead.

That night, huddled under my down comforter, we made love with most of our clothes on—“socks-on sex,” Graham called it. Once I rolled onto my side, he folded his body into the same shape as mine. He always liked falling asleep with me in his arms.

“You know, it’s probably raining in Hawaii,” I said, watching the snow gathering on the windowsill.

“And the roosters would be waking us up soon,” Graham mumbled, already fading.

“And I’d be really sunburned,” I pointed out.

“I still wish we never left,” he said, adding, “I love you,” before drifting off to sleep.

“I think you’re pretty great, too,” I whispered, squeezing his arm where it crossed over my heart.

But from the way Graham’s breathing had settled into a pattern, I could tell he hadn’t heard me—lately, he’d been nodding off long before me.

—

I KNEW IT was becoming a problem that I hadn’t told Graham I loved him. Every time he said it, I felt his hopeful anticipation and then the crushing letdown when I couldn’t give him the same caught-up-in-the-moment response. I thought going along with his “She loves me/She loves me not” series would diffuse some of that tension—not to mention give him a new project to work on. But after a while, it just seemed to shine a spotlight on the question I hadn’t answered.

I told myself it was a timing issue: Graham was more impulsive than me, so it made sense that he’d blurted it out after two weeks. But deep down I knew that wasn’t the only reason I was proceeding with caution, so I decided I should tell him why I was holding back. Being a writer, I thought I could explain myself more clearly in an email, so late one night I sat down at my computer and tried.

It took a few paragraphs to wind up to the topic I’d been avoiding, finally addressing it head-on.

I’m sorry in advance if this upsets you or makes you feel like you can’t get beyond your past, but it’s taking me time to trust that you don’t currently have a problem with drugs or alcohol—and to figure out whether I can live with the uncertainty that I’ll never be sure it won’t be a problem again. I know you’ve been very open with me about your past, and I’m glad you have, but it’s still a very unsettling issue to deal with when you’re entering into a relationship. That’s the main reason I’ve been trying to slow things down….

It was probably a mistake to put all that in an email, but I was having a hard time bringing it up in person, or on the phone. It was still that era when people wrote emails as if they were rediscovering the lost art of writing letters, so when I mustered up the courage to share my insecurities, email seemed like a safer way to open the door.

The thing is, I didn’t really think Graham was using at that point. I trusted that he wouldn’t hide it from me, or that I’d be able to tell. Even though my experience with drugs was limited—I’d smoked pot, but I’d never tried anything else floating around at parties—I wasn’t completely naïve about their effects. And Graham’s mood swings sometimes made me wonder what exactly was influencing his highs and lows.

The next morning, he woke me up with a call.

“I got your email,” he said, immediately launching into a defense. “And I understand what you’re getting at and why you might have some doubts about me, but I don’t want my past to dictate what you feel about us being together. I’ve been really open and honest with you about everything—trust me, the last thing I want is to go down that path again. It was too traumatic and too painful and I can’t believe you think I’d hide—”

“I didn’t say I thought you were hiding anything from me,” I interrupted, still groggy from my sleepless night. “I said it’s hard for me to deal with the fact that you might start drinking or using again.”

“You said currently have a problem.”

I rolled over, looking at my alarm clock: 7:23 A.M. Graham must’ve waited as long as he could before picking up the phone.

“Well, sometimes when I come over there are empty beer bottles on the table. It makes me wonder what you’re up to when I’m not around.”

“Just because I have people over who have a beer occasionally doesn’t mean I’m drinking,” Graham said, his voice getting louder, and more emphatic. “You can’t really expect me to ditch all of my pals who drink. You drink at my house or when we’re out.”

That was true. After working hard all week I was usually ready for a drink by the time I got to Graham’s place on Friday night. He always said it didn’t bother him, but maybe I was being too cavalier.

“If you don’t want me to drink when I’m with you I won’t,” I said, hoping he wouldn’t actually take me up on that offer. “But that’s not really the issue.”

“Then what is the issue? I hate that word. That’s such an American thing, having all these issues.”

I hesitated, trying to figure out how to cross this minefield without Graham exploding.

“I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have said ‘currently.’ The point I was trying to make is that one of the reasons I’ve wanted to take things slower is that I do sometimes worry about what’s going to happen five or ten years from now. People fall off the wagon, they relapse after being clean for decades. You can’t pretend it’s not a possibility.”

I could hear Graham suck in a breath before speaking, delivering his monologue without a pause.

“Listen, Susan—If you’re already worrying about what could happen five years from now, there’s an endless number of things you can add to the list. I could get knocked off my bike and end up in a coma, some lunatic could push you in front of a train. I just want to love you and for you to love me back. I know we can be happy together but you’ve got to want it, too. You can’t keep dwelling on all the negative things that might happen. Why don’t you focus on what’s good in your life? What’s good about us.”

And that’s how Graham threw me off the trail: It wasn’t his problem we were talking about, it was mine.

By the time we hung up, we had moved on to discussing all the stress in my life—the book, my worries about money, the constant pressure to convince editors to give me work. Graham was reassuring; I cried. I felt bad about putting him on the spot.

Frankly, he was righ

t that I worried too much about worst-case scenarios. “Smile, it might never happen,” he’d say, whenever he caught me lost in some gloomy thought. I liked that he made me see things I wanted to change—it meant that he really knew me, and wasn’t afraid to speak up. But I did worry about Graham’s sobriety over the long haul.

It felt like getting involved with someone whose cancer was in remission: There was always a chance that the tumor could come back with a vengeance. But then again, didn’t cancer survivors (or recovering addicts) deserve to be loved?

Ironically, neither of us remembers exactly when I first said, “I love you,” or what prompted me to finally utter those words. But it must’ve happened just after our talk, because a few days later Graham sent me an email saying he wanted to take some more “SLM/SLMN” pictures—our shorthand for his “She loves me…” project—ending his message by saying, “Now it can be SLM…SLMLoads.”

And I did love Graham. Maybe I expressed it in a more understated way than he did, but that didn’t make my feelings any less real. In fact, I sometimes thought that what I felt was more authentic, because I’d waited until I really meant it. Our gestures of love were just different.

He emailed me pictures of graffiti hearts he found painted on the sides of buildings; I cooked dinner for him, packing up leftovers he could reheat when I wasn’t there. He cut up the listings in the arts section of The New York Times, presenting me with tiny clippings of things to do when he brought me coffee in bed. But I was the one who followed through and bought tickets—he had ideas, I made plans.

It’s not so much that we were opposites who attracted; it’s more that each of us was missing something in our lives, and along came someone with the pieces that fit. I wouldn’t have filled out an online dating profile and come up with anyone like Graham, and I’m sure he wouldn’t have been matched with me. That’s partly why I had never embraced those sites. In my mind, falling in love wasn’t about meeting someone with all the characteristics you thought you wanted. It was about finding someone you didn’t realize you needed—or at least, that’s what Graham was for me.

Chancers

Chancers